Water Pressure Management Valves: Performance and Use

Aug 06, 2025

With rapid urbanization, the stability and safety of water supply systems have become increasingly critical. As essential components of these systems, valves play a key role in ensuring operational efficiency and reliability. This paper systematically evaluates the critical role of various regulating valves in managing water pressure and flow, based on experimental testing and real-world operational analysis. Based on data collection and field validation, this study provides selection recommendations for typical scenarios, offering a scientific basis for choosing suitable valves in water supply systems.

1. Overview

Driven by the National Water Network Construction Planning Outline, water supply networks have expanded in scale and coverage, effectively meeting the growing water demands of urban populations. However, aging infrastructure and high leakage rates remain significant challenges in many older districts. As technologies such as the Internet of Things and big data are integrated, water supply systems are becoming increasingly intelligent, driving the need for corresponding advancements in valve technology. As essential control devices within pipeline networks, valves—when properly regulated—optimize water flow, minimize losses, and enhance system efficiency. In modern applications, they must operate in coordination with sensors and intelligent control systems. This paper explores the optimized application of valves within pipeline networks. It begins by analyzing the use cases and technical characteristics of various valve types to guide model selection and system integration. It then presents test results for flow and pressure regulating valves, self-operated pressure regulating valves (T-type and Y-type), and V-type ball valves, based on experiments conducted at a specialized testing facility. These results are integrated with field data to validate valve performance under real-world conditions, providing a solid basis for more informed and practical valve selection.

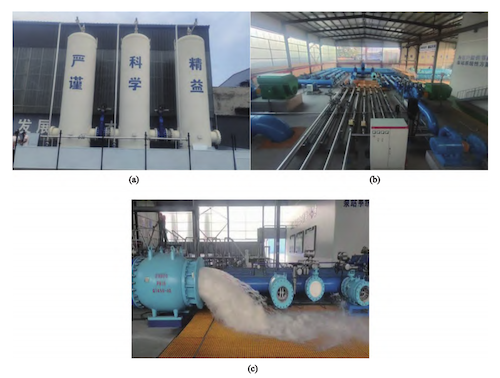

The Valve Dynamic Performance Testing Center project, funded with a total investment of 20 million RMB, was developed in close partnership with Changsha University of Science and Technology. The control programs were independently designed and developed. Eighteen water flow test pipelines, ranging in diameter from DN50 to DN800, were constructed. Five horizontal centrifugal pumps and five vertical multistage pipeline pumps were used to maintain stable water flow during testing. The test center supports valve testing across a broad range of sizes—from DN50 to DN800—and pressure classes ranging from PN6 to PN63, providing industry-leading capabilities for dynamic performance testing of large-diameter valves. It can evaluate more than 40 valve performance indicators (see Figure 1 for details).

(a) Energy storage tank (b) Front view of the test pipeline area (c) DN300–DN800 test pipeline outlet

Figure 1. Actual View of the Test Base

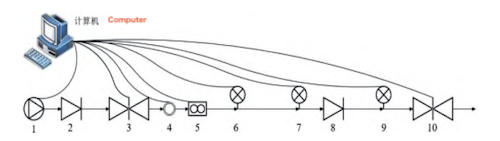

During testing, the valve was first installed on the corresponding pipeline diameter and fully opened. The pipeline pressure was then adjusted to 1.0 MPa, and the flow rate set to the maximum economical flow for that diameter. Once the pressure and flow stabilized, the valve opening was gradually adjusted from 100% to 0% in 10% increments. At each step, upstream and downstream pressures, flow rate, valve vibration, and noise levels were recorded. The overall test setup is shown in Figure 2 and includes the data acquisition card and software system. Arrows indicate the direction of water flow within the pipeline.

Field sampling was performed under typical operating conditions for both flow and pressure regulating valves as well as intelligent self-operated pressure regulating valves. Key performance parameters—including water pressure, flow rate, vibration, and noise—were analyzed to verify valve reliability under real-world conditions. Additionally, the potential for integrating intelligent valves was explored through data acquisition and actuator linkage.

1. Water Pump 2. Multi-function Water Pump Control Valve 3. Electric Valve 4. Temperature Sensor 5. Electromagnetic Flowmeter 6. Pressure Sensor (Straight Pipe Section Before Valve) 7. Pressure Sensor (Before Valve) 8. Flow Control Valve 9. Pressure Sensor (After Valve) 10. Electric Valve

Figure 2 Schematic Diagram of the Test Setup

Tests were conducted on multi-orifice flow and pressure regulating valves, intelligent self-operated pressure regulating valves (including T-type and Y-type), and V-type ball valves. The collected data were then analyzed accordingly.

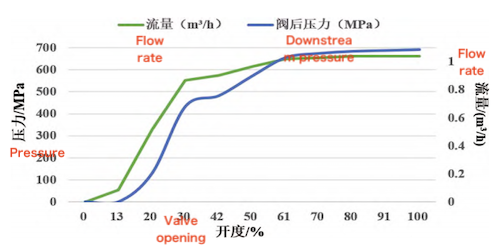

3.1 Multi-Orifice Flow and Pressure Regulating Valve

Figure 3 presents a schematic diagram of the multi-orifice flow and pressure regulating valve. Test results indicate that the valve cage allows rapid adjustment within the 10% to 30% opening range. Once the opening reaches 30%, the flow rate stabilizes at 553 m³/h, entering a slower adjustment range. For higher flow demands at the outlet, the valve can be opened beyond 60%. As shown in Table 1, when the valve opening is below 40%, the pressure differential reaches 0.2 MPa, accompanied by noticeable noise. When the opening falls below 30%, noise levels increase significantly, indicating that the valve operates most effectively at openings above 40%. Figure 4 illustrates that the multi-orifice design disperses fluid kinetic energy and reduces the nonlinear effects of turbulence on pressure, resulting in superior opening–flow characteristics compared to opening–pressure characteristics. Additionally, the flow control performance is affected by the piston cage’s opening pattern, area, and position, all of which influence the opening–flow and opening–pressure characteristic curves.

Figure 3 Multi-Orifice Flow and Pressure Regulating Valve

Table 1 Test Data for Multi-Orifice Flow and Pressure Regulating Valve

|

Opening (%) |

Flow (m³/h) |

Valve Outlet Pressure (MPa) |

Remarks |

|

0 |

0 |

– |

– |

|

13 |

55 |

0 |

Severe noise |

|

20 |

327 |

0.203 |

Severe noise |

|

30 |

553 |

0.681 |

Severe noise |

|

42 |

574 |

0.757 |

Noise observed |

|

50 |

615 |

0.898 |

– |

|

61 |

650 |

1.029 |

– |

|

70 |

655 |

1.059 |

– |

|

80 |

660 |

1.074 |

– |

|

91 |

662 |

1.080 |

– |

|

100 |

662 |

1.086 |

– |

3.2 Intelligent Self-Operated Pressure Regulating Valve

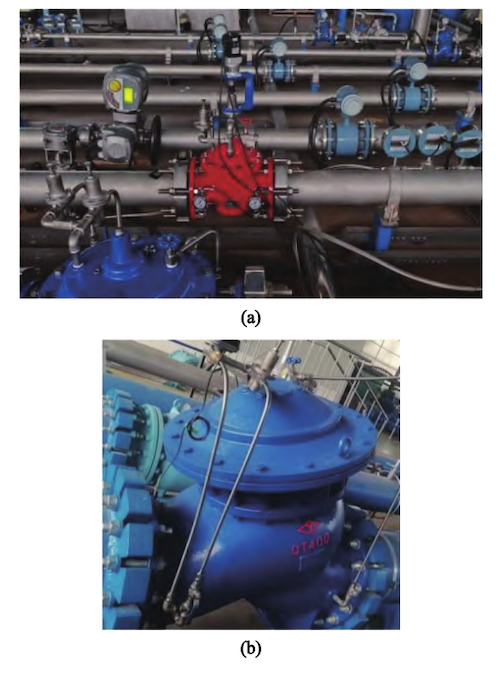

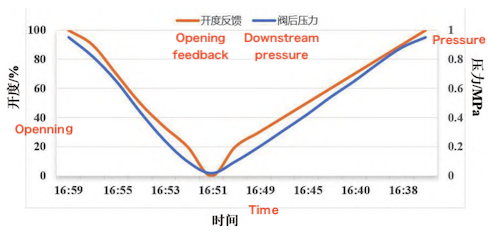

Figure 5(a) shows a red T-type self-operated intelligent pressure regulating valve. During the test, the upstream pressure was maintained at 1.0 MPa. The results are summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 6. At a valve opening of 50%, the downstream pressure was 0.42 MPa, corresponding to a pressure reduction ratio of 58%. At this stage, noise was detected in the valve body. When the valve opening was reduced to 40%, the downstream pressure dropped to 0.31 MPa, corresponding to a pressure reduction ratio of 69%, and cavitation occurred inside the valve. This condition is unsuitable for prolonged operation. Figure 6 shows that the pilot valve opening and downstream pressure change in the same direction; however, their relationship is piecewise linear due to cavitation. Moreover, downstream pressure stability was poor under repeated valve opening cycles. For example, at a 90% opening, the pressure deviation reached ±0.03 MPa.

Figure 4 DN350 Flow Control Valve Test Data Curve

(a) T-type Self-Operated Intelligent Pressure Regulating Valve (b) Y-type Self-Operated Intelligent Pressure Regulating Valve

Figure 5 Intelligent Self-Operated Pressure Regulating Valves

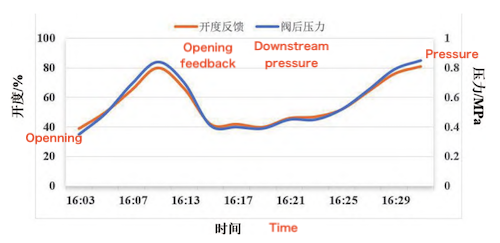

Figure 5(b) shows a Y-type self-operated intelligent pressure regulating valve. The test data are summarized in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 7. The results show that pilot valve opening and downstream pressure trends are consistent, exhibiting a piecewise linear relationship due to cavitation. When the valve opening ranged from 39% to 81%, the downstream pressure deviation during repeated openings was only 0.005 MPa. Moreover, the downstream pressure responded linearly to each unit change in valve opening, indicating excellent regulation performance.

Table 2 Test Data for T-Type Self-Operated Intelligent Pressure Regulating Valve

|

Acquisition Time |

Valve Outlet Pressure (MPa) |

Valve Opening Feedback (%) |

Valve Status |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:56 |

0.82 |

90 |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:55 |

0.65 |

70 |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:54 |

0.44 |

50 |

Noise occurred |

|

2024/9/14 16:53 |

0.25 |

34 |

Loud noise, valve vibration, fluctuating outlet pressure |

|

2024/9/14 16:52 |

0.10 |

20 |

Severe cavitation and pipeline vibration |

|

2024/9/14 16:51 |

0.02 |

0 |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:50 |

0.10 |

20 |

Severe cavitation and pipeline vibration |

|

2024/9/14 16:49 |

0.20 |

30 |

Severe cavitation, pipeline vibration |

|

2024/9/14 16:47 |

0.31 |

40 |

Loud noise, valve vibration, downstream pressure fluctuation |

|

2024/9/14 16:45 |

0.42 |

50 |

Noise |

|

2024/9/14 16:44 |

0.54 |

60 |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:40 |

0.65 |

70 |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:39 |

0.77 |

80 |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:38 |

0.88 |

90 |

– |

|

2024/9/14 16:37 |

0.95 |

100 |

– |

Figure 6 T-Type Self-Operated Intelligent Pressure Regulating Valve Test Data Curve

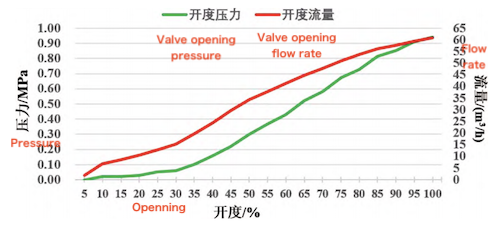

Table 4 and Figure 8 present the test data for opening, flow, and pressure of a DN100 V-type ball valve. Analysis of the data shows that the opening–flow characteristic of the V-type ball valve is nearly linear, demonstrating better adjustment sensitivity than its opening–pressure characteristic. In the opening–flow test, the flow rate increased steadily by approximately 2 m³/h for every 5% increase in valve opening between 10% and 30%. The flow rate increased by approximately 4 m³/h per 5% increment between 30% and 50%, and by 3 m³/h per 5% increment between 50% and 90%. The valve’s adjustable opening range of 10% to 90% makes it well suited for precise flow control applications, such as refrigeration systems. However, for pressure regulation, it needs to be used in conjunction with other valves. In the opening–pressure test, the correlation between valve opening and pressure was poor below 85% opening, and pressure adjustability was inconsistent across the range. Therefore, V-type ball valves are unsuitable for pressure regulation based solely on valve opening.

Figure 7 Y-Type Self-Operated Intelligent Pressure Regulating Valve Test Data Curve

Table 4 DN100 V-Type Ball Valve Test Data

|

Opening (%) |

Pressure (MPa) |

Flow (m³/h) |

Opening (%) |

Pressure (MPa) |

Flow (m³/h) |

|

5 |

0.00 |

2.00 |

55 |

0.368 |

37.89 |

|

10 |

0.02 |

6.78 |

60 |

0.43 |

41.20 |

|

15 |

0.02 |

8.62 |

65 |

0.52 |

44.68 |

|

20 |

0.03 |

10.62 |

70 |

0.581 |

47.68 |

|

25 |

0.05 |

12.82 |

75 |

0.675 |

50.96 |

|

30 |

0.06 |

15.18 |

80 |

0.728 |

53.58 |

|

35 |

0.10 |

19.77 |

85 |

0.814 |

56.10 |

|

40 |

0.16 |

24.55 |

90 |

0.854 |

57.65 |

|

45 |

0.22 |

29.70 |

95 |

0.908 |

59.40 |

|

50 |

0.30 |

34.32 |

100 |

0.939 |

60.77 |

Figure 8 V-Type Ball Valve Test Data Curve

Operational verification was conducted on both the multi-nozzle flow and pressure regulating valve and the Y-type self-operated intelligent pressure regulating valve.

During water supply operations, a water company experienced issues such as pipe bursts and water leakage. To address these problems, a DN1200 flow regulating valve was installed. The company set the following operational requirements:

- The valve’s downstream pressure must be adjustable at different times to lower excessive pressure while maintaining sufficient supply, thus preventing pipe bursts and water loss.

- Manual and automatic switching should be supported to facilitate both local debugging and automatic operation.

- Remote monitoring should be enabled, with valve opening, pipeline flow, and pressure parameters transmitted to a cloud platform via the Internet of Things (IoT). The data should be accessible online, and authorized personnel should be able to remotely open and close the valve.

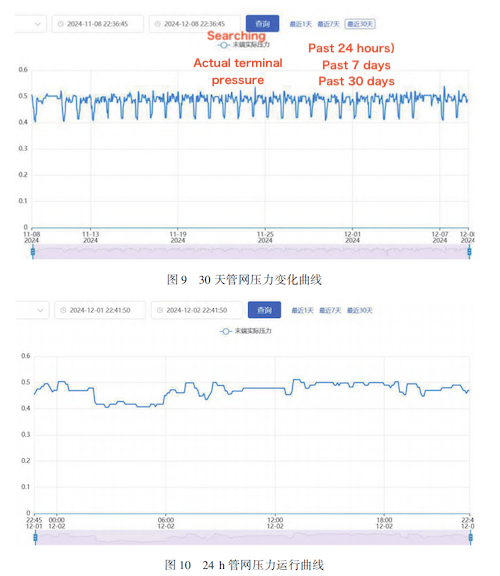

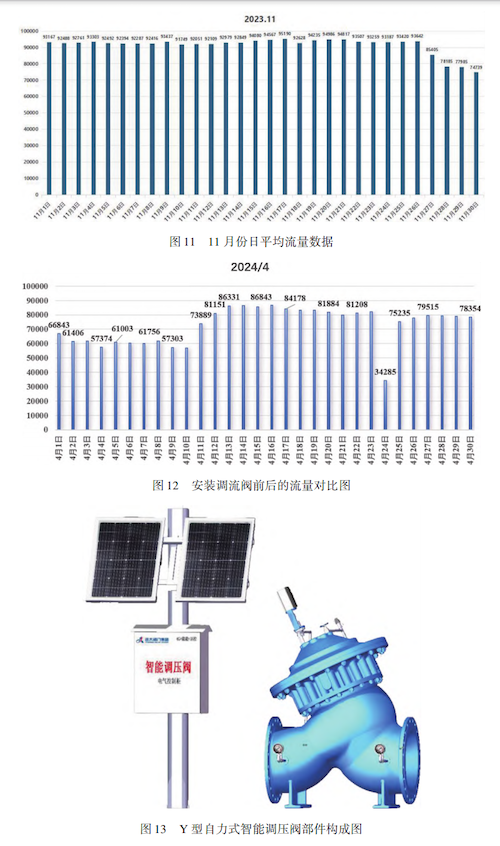

To meet these requirements, a remote pressure sensor with a DN100 diameter was installed at the most critical point, located 7 km downstream of the valve. Based on preset time-based pressure values, the flow and pressure regulating valve automatically adjusted its opening to control the pipeline pressure. Based on data monitored over time after installation, Figure 9 shows that pipeline pressure control remained stable and reliable throughout the 30-day period. At 00:46:00, the water pressure remained steady at 0.41 ± 0.01 MPa, effectively resolving the issue of high-pressure pipe bursts at night. During other periods, the pressure was maintained at 0.48 ± 0.02 MPa, ensuring a stable water supply. Additionally, a comparison of flow data before and after installation revealed a significant reduction in water loss. Prior to installation (data from November 1 to November 26), the average daily flow rate was 97,000 m³ (Figure 11). After installation (data from April 11 to April 30, excluding maintenance on April 24), the average daily flow rate decreased to 85,000 m³ (see Figure 12), representing a reduction of 12,000 m³ per day. At a profit rate of 1.8 RMB per ton of water, this translates to an average daily cost saving of 21,600 RMB.

Figure 9: 30-Day Pipeline Pressure Change Curve

Figure 10: 24-Hour Pipeline Pressure Operation Curve

This valve was used under gravity-fed water supply conditions with a 200-meter elevation difference. Pressure regulation along the pipeline was necessary to lower network pressure and prevent pipe bursts caused by excessive pressure. To address this, seven intelligent pressure-regulating valves were installed throughout the pipeline network. Each valve was configured to ensure that the upstream pressure did not exceed 0.45 MPa, and clean electrical power was supplied for valve operation. In addition, the valves were equipped with real-time pressure and temperature monitoring. They automatically adjusted downstream pressure in response to changing operating conditions and activated a heating function when necessary. Figure 13 shows the components of the Y-type self-operated intelligent pressure-regulating valve. This system provides comprehensive data, including the overall pipeline layout, installation site elevation, valve diameter, upstream and downstream water pressure, battery charge level, voltage, photovoltaic generation voltage, pilot valve opening, bypass pipe water temperature, heating status, operation mode (automatic/manual), and ambient temperature. Since installation, the water pressure has remained stable, with a deviation within ±0.01 MPa. This demonstrates that the intelligent pressure-regulating system effectively achieves staged pressure reduction. It also enables real-time monitoring of valve opening, pressure, and temperature, and supports remote access and control.

Figure 11: Average Daily Flow in November

Figure 12: Flow Rate Comparison Before and After Installation of Flow Control Valve

Figure 13: Components of Y-Type Self-Operated Intelligent Pressure-Regulating Valve

This paper focuses on water pressure management valves in water supply networks. It first emphasizes the importance of valve technology in the intelligent development of water supply systems. Dynamic performance tests were conducted at an advanced testing center built with a 20 million RMB investment to verify the reliability and intelligent application potential of these valves. Test data for multi-nozzle flow and pressure regulating valves, T-type and Y-type self-operated intelligent pressure regulating valves, and V-type ball valves were analyzed to assess their performance characteristics. Finally, the application performance of the multi-nozzle and Y-type self-operated valves was validated under representative operating conditions.

The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Multi-nozzle flow and pressure regulating valves are suitable for flow and pressure regulation in water diversion and supply pipelines. The piston opening should be optimized according to specific operating conditions during use.

(2) T-type and Y-type self-operated intelligent pressure regulating valves are suitable for gravity-fed water supply systems. They provide stable pressure control, support remote monitoring and operation, and are well-suited for applications requiring intelligent management and energy efficiency. The T-type valve is suitable for applications with pressure differential ratios greater than 60%, while the Y-type valve performs best under conditions where the pressure differential ratio exceeds 80%.

(3) V-type ball valves exhibit favorable linear regulation characteristics and are well-suited for flow control applications such as refrigeration systems, heating return water, and various industrial processes.

When traditional mechanical valves are integrated with an Internet of Things (IoT) platform, real-time status monitoring and automated control become possible. This advancement contributes to the intelligent development of valve technology and provides significant benefits for pipeline network management.

Previous: Impact of Bonnet Flange Thickness on Control Valve Strength: A Finite Element Study

Next: Structural Design Optimization of Ultra-High-Pressure Ball Valves