High-Performance NiCr Corrosion-Resistant Ductile Iron Butterfly Valves

Sep 17, 2025

Abstract: By adding nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr) to molten iron during spheroidization and inoculation, this study developed a low-NiCr corrosion-resistant ductile iron with outstanding performance. The material has been successfully applied in butterfly valves. By optimizing the alloying element ratios and heat treatment process, the ductile iron’s corrosion resistance, mechanical properties, and machinability were significantly enhanced, allowing reliable operation in harsh environments such as chemical plants, wastewater treatment facilities, and seawater cooling systems. Test results demonstrate that the high-performance NiCr corrosion-resistant ductile iron attains a tensile strength of 560 MPa, a yield strength of 420 MPa, an elongation of 16%, a hardness of 208 HB, and a corrosion rate of just 0.065 mm/a, fully meeting the stringent requirements for butterfly valves under severe operating conditions. As industries impose increasingly stringent requirements for valve corrosion resistance—especially in chemical and wastewater systems and in power plants using seawater cooling—the demand for valves with superior corrosion resistance has risen sharply. Duplex stainless steel, prized for its exceptional corrosion resistance, has been widely used in offshore drilling platforms, ship propulsion systems, marine propellers, seawater desalination plants, chemical storage tanks, and other critical applications. However, employing duplex stainless steel as a corrosion-resistant material poses several challenges, including high production costs (around 50,000–80,000 yuan per ton), long manufacturing lead times (typically 10–14 weeks), and complex maintenance requirements, such as the frequent replacement of seals. For instance, a chemical company reported annual downtime and maintenance costs of up to 2 million yuan for its seawater cooling system due to valve corrosion. This underscores the urgent need for a new material that provides the necessary corrosion resistance while also offering lower cost and improved manufacturability. In recent years, the increasing focus on environmental protection, resource conservation, energy efficiency, emission reduction, and lightweight machinery has accelerated industrial restructuring. Aligned with national policy priorities supporting the development of advanced materials and high-tech industries, the research and development of new structural materials with high strength, excellent formability, and superior machinability has become an essential trend. Within this context, focus has increasingly turned to ductile iron. Developed in the 1950s, ductile iron is a high-strength cast iron in which spheroidal graphite is achieved through spheroidizing and inoculation treatments, significantly enhancing the material’s mechanical properties. Ductile iron exhibits strength comparable to that of ordinary carbon steel, combining the advantageous properties of both iron and steel. It is widely regarded as an engineering material offering high plasticity, strength, corrosion resistance, and wear resistance. China is currently the world’s largest producer of ductile iron, contributing approximately 30% of the global annual output. Advances in casting technology and improvements in quality control have further expanded its applications, allowing ductile iron components to perform reliably under extreme conditions, including heavy loads, low temperatures, fatigue, wear, and corrosion. Its use in marine environments has attracted increasing attention, prompting both domestic and international researchers to focus on developing corrosion-resistant grades of ductile iron. Corrosion-resistant ductile iron has become a research hotspot in the field of corrosion resistance because of its advantages, including simple smelting, low cost, and minimal environmental impact. It has been widely applied, for example, in valves of various sizes used in nuclear power plant circulating water cooling systems. To meet the stringent demands of marine corrosive environments, ductile iron has been further optimized to retain excellent mechanical properties while enhancing its corrosion resistance. Specialized grades, including corrosion-resistant ductile iron for marine environments and oxidation-resistant ductile iron for high-temperature oxidizing conditions, have already been successfully developed. By carefully controlling alloying elements such as Ni, Cr, and Mo, ductile iron can achieve enhanced plasticity, strength, corrosion resistance, and wear resistance, making it a highly promising engineering material with broad application and development potential. Cast iron corrosion primarily occurs through chemical and electrochemical processes. According to electrochemical corrosion theory, a single-phase, uniform microstructure offers superior corrosion resistance under the same conditions. However, in practice, producing cast iron with a completely uniform metallographic structure is unrealistic. Therefore, corrosion resistance can be improved by homogenizing the microstructure. In general, there are three primary approaches to enhancing the corrosion resistance of ductile iron:

Alloying – Adjusting the composition of the alloy to modify the electrochemical potential of the phases in the corrosive environment, thereby reducing the driving force of galvanic corrosion.

Protective Film Formation – Encouraging the formation of a dense, high-resistance corrosion layer on the material’s surface, especially a stable passivation film.

Graphite and Matrix Optimization – Refining the shape, size, and distribution of graphite particles and the surrounding matrix to reduce the formation of galvanic cells.

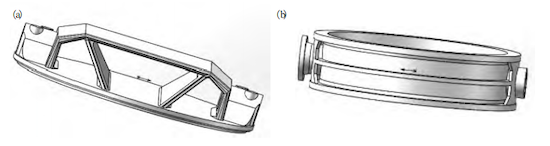

The corrosion-resistant ductile iron valve body and butterfly disc produced by a specific manufacturer serve as the core components of a butterfly valve supplied to a domestic chemical company. The 3D casting models are shown in Figure 1, weighing 6.9 tons and 7.8 tons, respectively. The wall thickness of the valve body exceeds 60 mm, with a maximum thickness greater than 100 mm. The valve body has a maximum diameter of 3400 mm, and the butterfly disc measures 2900 mm. These corrosion-resistant ductile iron valve bodies are intended for mass production.

The castings are made of alloyed ductile iron and must satisfy strict performance standards. Defects such as cracks, cold shuts, or shrinkage that could compromise performance are strictly prohibited. The carbide content in the casting’s microstructure must not exceed 1%, and the graphite nodularity must be at least 90%. The corrosion rate of the castings, determined through a full-immersion test in 3.5% NaCl solution, must not exceed 0.25 mm/year. After assembly, the castings must pass a hydrostatic pressure test of 2.4 MPa for 30 minutes with no leakage.

Figure 1. 3D casting models

Too low a carbon content in ductile iron hinders graphitization and reduces the fluidity of the molten iron, whereas excessive carbon can lead to graphite flotation. Silicon strongly promotes graphitization, with each 0.1% increase in Si raising the carbon equivalent (CE) by approximately 0.03%. Excess silicon dissolves in ferrite, causing lattice distortion (with the lattice constant changing by approximately 0.002 nm), which promotes the formation of a ferrite matrix and enhances casting elongation. When the silicon content increases from 2.0% to 2.8%, the elongation correspondingly increases from 8% to 16%. However, excessive silicon raises the carbon equivalent too much, causing poor spheroidization and graphite flotation, which increase material brittleness and reduce the casting’s load-bearing capacity. Manganese strengthens the pearlite matrix but tends to segregate at grain boundaries, which reduces both plasticity and toughness. Sulfur reacts with the spheroidizer; if present in excess, it reduces residual magnesium, causing defects such as poor spheroidization, slag inclusions, and subcutaneous porosity. In addition, a high sulfur content reduces the corrosion resistance of cast iron. Phosphorus is another detrimental element. The phosphorus eutectic readily accumulates at eutectic boundaries, significantly reducing the overall mechanical properties of ductile iron. Nickel exhibits a decarburizing effect and has a low affinity for carbon, making carbide formation less likely. It refines pearlite, promotes the formation of a pearlitic matrix, and, when added in small amounts, forms a dense protective surface film. Nickel improves the corrosion resistance of ductile iron in both reducing and oxidizing environments. Chromium is soluble in iron but readily forms carbides. Like nickel, it raises the matrix’s electrode potential and forms a protective oxide layer on the surface, thereby enhancing the corrosion resistance of ductile iron. The chemical composition of the alloyed ductile iron designed for this study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Chemical Composition of the Casting (wt%)

|

Element |

C |

Si |

Mn |

P |

S |

Ni |

Cr |

Mg |

RE |

|

Content |

3.4–3.8 |

2.2–2.8 |

≤0.3 |

≤0.04 |

≤0.025 |

2–4 |

0.2–0.5 |

0.03–0.06 |

0.02–0.04 |

The molten iron was smelted in a medium-frequency furnace using high-quality carbon scrap steel (C 0.25%–0.35%, S ≤ 0.025%). Impurities in the molten iron were strictly controlled. The raw materials consisted of high-grade Q10 pig iron (C 4.2%–4.5%, Si 1.2%–1.5%), a low-sulfur, low-nitrogen graphite recarburizer, and high-purity electrolytic nickel plate (Ni ≥ 99.9%). Smelting was performed in the following sequence: pig iron, scrap steel, recarburizer, alloy, and recycled material. Once the molten iron became clear and reached 1400–1430°C, samples were taken for analysis, and the alloying elements were adjusted as needed. The temperature was then raised to 1500–1530°C and held for 5–10 minutes. Spheroidizing and inoculation were carried out using the ladle-injection method. A light arsenic–medium magnesium alloy was employed as the spheroidizer, while silicon, barium, calcium, and standard 75% ferrosilicon granules were used as inoculants. The addition rates were 1.3%–1.6% for the spheroidizer and 1.0%–1.3% for the inoculant. The ladle was preheated, and the molten iron was brought to 1400–1430°C. At 300–500 °C, the spheroidizing agent and inoculant were added proportionally to the inner surface of the spheroidizing ladle. Once the molten iron reached 1450–1480 °C, it was removed from the furnace for the spheroidization process. During spheroidization, the remaining inoculant was added in separate batches to enhance its effectiveness. After spheroidization, the slag was promptly removed, and samples were collected for analysis. Once settled, the molten iron was poured at a temperature of 1350–1380°C. During casting, a silicon–barium–calcium inoculant with a particle size of 0.2–0.5 mm was added at a proportion of 0.13%–0.14%. This further enhanced inoculation, refined the microstructure, and minimized the risk of graphite fading.

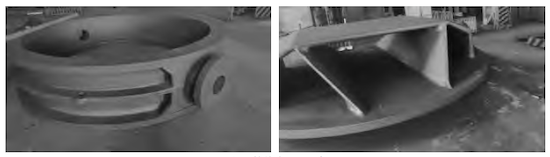

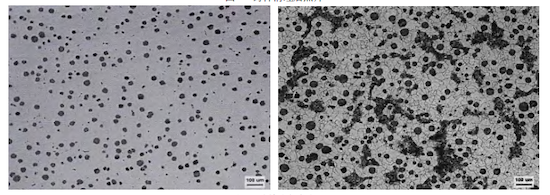

After cleaning, the casting underwent low-temperature graphitization annealing at 720–1010°C for 10–12 hours, resulting in a microstructure predominantly composed of ferrite. The cleaned casting is shown in Figure 2. After annealing, samples were taken for microstructural and metallographic analysis. The results, shown in Figure 3, confirmed a spheroidization grade of 2 (90%–95% nodularity, graphite size 6), with ferrite content ≥70% and carbide ≤1%. The specific mechanical properties, presented in Table 2, met all design requirements. Furthermore, after being shipped to the customer’s site for processing and assembly, the castings successfully passed a hydrostatic test at 2.4 MPa for 30 minutes without any leakage, fully meeting all technical requirements.

Table 2 Mechanical Properties of Specimens

|

Test Item |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Yield Strength (MPa) |

Hardness (HB) |

Elongation (%) |

|

Required Value |

≥450 |

≥310 |

160–260 |

>3 |

|

Test Value |

560 |

420 |

208 |

16 |

To evaluate the material’s corrosion resistance, both the castings and test specimens were subjected to corrosion tests. Full-immersion tests were conducted in a 3.5% NaCl aqueous solution. A total of 12 parallel specimens were prepared and divided into two groups, QT1 and QT2. Six specimens were subjected to a 72-hour corrosion test, while the remaining six underwent testing for 168 hours. Before testing, the specimens were cleaned with acetone, dried, and weighed. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Corrosion Test Results in 3.5% NaCl Aqueous Solution

|

Sample No. |

Test Time (h) |

Original Weight (g) |

Post-Corrosion Weight (g) |

Corrosion Rate (mm/year) |

|

QT1-1 |

72 |

35.6566 |

35.6458 |

0.066 |

|

QT1-2 |

72 |

35.3440 |

35.3327 |

0.069 |

|

QT1-3 |

72 |

35.4596 |

35.4489 |

0.066 |

|

QT1-4 |

168 |

34.6551 |

34.6286 |

0.069 |

|

QT1-5 |

168 |

35.8876 |

35.8618 |

0.067 |

|

QT1-6 |

168 |

32.7184 |

32.6949 |

0.062 |

|

QT2-1 |

72 |

34.5422 |

34.5319 |

0.064 |

|

QT2-2 |

72 |

35.2375 |

35.2296 |

0.065 |

|

QT2-3 |

72 |

35.1325 |

35.1219 |

0.065 |

|

QT2-4 |

168 |

34.7622 |

34.7385 |

0.063 |

|

QT2-5 |

168 |

35.0206 |

34.9967 |

0.063 |

|

QT2-6 |

168 |

34.1457 |

34.1221 |

0.062 |

Analysis of the data in Table 3 reveals the following:

Time effect: There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the average corrosion rate of the 168-hour group (0.065 mm/a) and the 72-hour group (0.066 mm/a), indicating that the passivation film exhibits good stability.

Batch consistency: The deviation between the QT1 and QT2 groups was less than 5%, demonstrating excellent process stability.

The successful development and application of NiCr corrosion-resistant ductile iron butterfly valves have provided valuable insights and technical experience for the butterfly valve industry. These butterfly valves are expected to maintain their advantages in terms of cost, performance, corrosion resistance, and quality stability. However, the domestic valve industry still lags behind leading international technologies. Consequently, relevant sectors should actively pursue the development of new materials and technologies to enhance their competitiveness in both domestic and global valve markets.

Figure 2. Photograph of the casting after cleaning

Figure 3. Metallographic structure of the test specimen

Previous: Optimized Design and Performance of Electric Gate Valves for Nuclear Power Plants

Next: Processing Thin-Walled Parts for Large-Diameter Soft-Seated Butterfly Valves